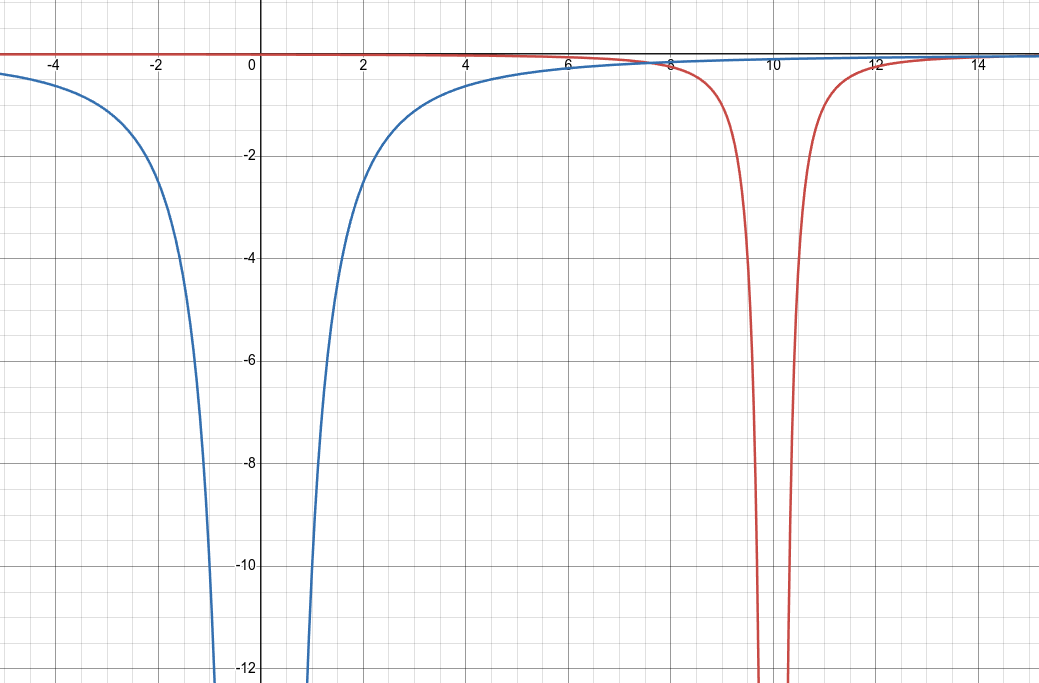

Here we have two different particles in the potential energy field (AKA spacetime). Blue has ten times the mass of red. The force they exert on each other is the inverse square curvature of the field (mass/distance^2), propagated at the speed of causation. How do they move?

Well, assuming a stationary start, they move towards each other. The velocity path they each follow is the sum of the force (acceleration) acting upon them. That propagates as a hyperbola (mass/distance). Here’s what that looks like before the motion starts.

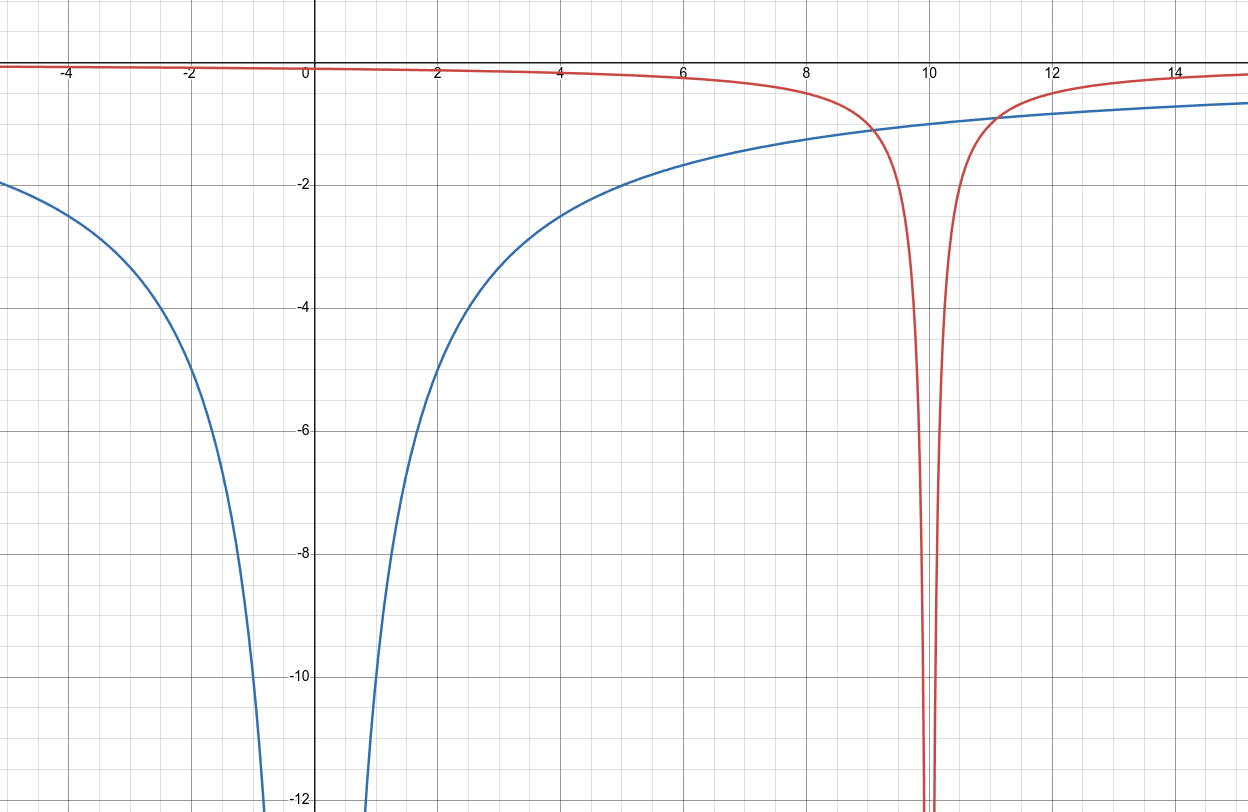

Of course, as they move towards each other, their velocities will increase, and their curves will be gradually compressed in the direction of motion, and stretched out in the opposite direction.

The velocity of a particle is a localized gradient. This gradient has its center at the particle’s mass (which is, of course, subtracted from the potential energy), and is angled down (less potential, more kinetic) in the direction of motion, up in the opposite. The gradient is entirely localized, and does not exist outside the particle’s boundaries (±1 from its center). The combination of this inner energy gradient and the outer curvature is the cause of blue and red shift.

Note that the force acting upon each particle doesn’t care about its mass. The only thing that matters is the curvature of the potential energy field, which is caused by the other particle. But notice how much more the heavier particle curves the field. This causes the lighter particle to accelerate faster than the heavier, and move further before they meet.

Mass curves spacetime. Curvature accelerates mass.

How much does the curvature accelerate the particle? You simply integrate the curvature along the path, and then divide by the time it takes the particle to follow that path. After all, a slower moving particle has more time to be influenced by the curvature than a fast moving one. How do you find the time? Form the particle’s velocity, of course.

The kinetic energy is altered by the path curvature of the potential energy over time. Or, more simply, the momentum gradient is altered by the potential gradient over time.

This is equivalent to the action, which in units is energy multiplied by time (mass * velocity[kinetic] * velocity[potential] * time). Note that in actual use, the mass can often be factored out, because it is both invariant and irrelevant in most cases. (The mass of a satellite doesn’t much affect the motion of the Earth, just as the sun isn’t noticeably perturbed by the orbit of Mars.)

Why does action have the same units as angular momentum? Because what you’re really doing is rotating the angle of the momentum gradient. The principle of least action applies to particles moving in the potential energy field (AKA spacetime) in exactly the same manner as in quantum physics. It is one of the foundations of the equations of general relativity.

Aside 1 - The Heisenberg uncertainty principle shows that the edges of a particle, where the inner kinetic gradient meets the outer potential gradient, are a smooth curve instead of a sharp discontinuity.

Aside 2 - The same principles hold true for the electromagnetic field, except that like charges (those that distort the field’s zero base line in the same direction) repel and opposites attract.

Aside 3 - A stable orbit is that which holds the angle of the momentum gradient constant after one full orbit (which may be different from one rotation). This is a form of quantization.

Copenhagen interpretation delenda est!

Reposted from my substack.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I reserve the right to remove egregiously profane or abusive comments, spam, and anything else that really annoys me. Feel free to agree or disagree, but let's keep this reasonably civil.